I watched a startup burn through $2 million developing a "superior" barrier film for chips. The lab tests were perfect. Oxygen transmission rates beat industry standards. But when they tried running it on Ishida filling lines, the film jammed every 50 bags.

Most chips use metallized OPP (oriented polypropylene) films in multi-layer structures1, not because it’s optimal, but because it forgives the 15-millisecond sealing dwell time variations that dominant VFFS (Vertical Form Fill Seal) machines produce at scale. The real challenge isn’t barrier performance2—it’s reverse-engineering your film to match the sealing jaw temperature curves of Ishida, Bosch, or Tokyo Automatic Machinery, the three manufacturers controlling 80% of global filling lines since 2008.

Here’s the uncomfortable truth: you can’t design chips packaging in isolation. I’ve spent 15 years in sustainable flexible packaging3, and the biggest mistake I see is companies optimizing for material properties while ignoring the machinery reality. Let me show you what actually matters.

Why Machine Compatibility Matters More Than Barrier Properties?

When I first started advising food brands on packaging, everyone asked about oxygen permeability. No one asked about their co-packer’s equipment manufacturer. That’s backwards.

The Three-Manufacturer Lock-In Reality

Three companies dominate chip filling equipment worldwide: Ishida (Japanese multihead weighers), Bosch Packaging (German VFFS systems), and Tokyo Automatic Machinery. If your film doesn’t run smoothly on their machines, you don’t have a business.

These machines weren’t designed for today’s sustainable materials. They were optimized for metallized BOPP in the 1990s. Their sealing jaws heat up and cool down at specific rates. Their forming collars expect certain film stiffness. When you try running a new compostable film, you’re fighting 30 years of mechanical assumptions.

Sealing Temperature Curves vs. Lab Test Data

Here’s what the lab tests don’t show you: a VFFS machine’s sealing jaws contact the film for 12-18 milliseconds at temperatures between 160-200°C. But that contact time varies by ±15 milliseconds depending on line speed, ambient humidity, and how worn the jaws are.

Metallized OPP dominates because its melting point (160°C) and heat conductivity create a wide process window. If the jaws are slightly cooler or contact time is shorter, you still get a seal. Compare that to some bio-based films where the window is 5°C wide. One degree off and you get leakers or weak seals.

I’ve tested films where oxygen transmission looked identical in a lab chamber (23°C, 50% RH, static conditions). On a production line at 120 bags per minute with temperature fluctuations, one film had a 2% seal failure rate and the other had 18%. The difference? How forgiving the material was to real-world machine variance.

Common Chips Packaging Material Structures

Let me break down what’s actually being used, and why each structure exists.

Metallized OPP Films (Industry Standard)

The typical chip bag is not a single plastic. It’s a laminate of three layers:

| Layer | Material | Function |

|---|---|---|

| Outer | PET (12 microns) | Printability, puncture resistance |

| Middle | Metallized OPP (20 microns) | Oxygen/moisture barrier, light block |

| Inner | PE or CPP (40-60 microns) | Heat seal, grease resistance |

Why this specific structure? The PET outer layer takes high-resolution rotogravure printing. The metallized barrier keeps oxygen below 0.5 cc/m²/day (chips go stale above 2 cc/m²/day). The inner PE layer melts at 110-130°C, creating the seal without burning through when VFFS jaws hit 180°C.

Total thickness is 70-90 microns. Thinner than that and you get pinholes during shipping. Thicker and the film won’t form properly around the VFFS collar.

Multi-Layer Laminates (PE/BOPP/PET Combinations)

Some premium brands use 5-7 layer coextruded films4 instead of laminates. The advantage is no delamination risk (when layers separate in high humidity). The disadvantage is you need specialized extrusion equipment and minimum order quantities jump to 5+ tonnes per SKU.

I worked with a Korean snack brand that switched from laminate to coex. Their shelf life went from 9 months to 14 months because there were no micro-gaps between layers for oxygen to creep through. But their MOQs tripled and lead times went from 3 weeks to 8 weeks.

For smaller brands (under 50 tonnes annual volume), laminates make more sense. For multinationals, coex becomes cost-effective.

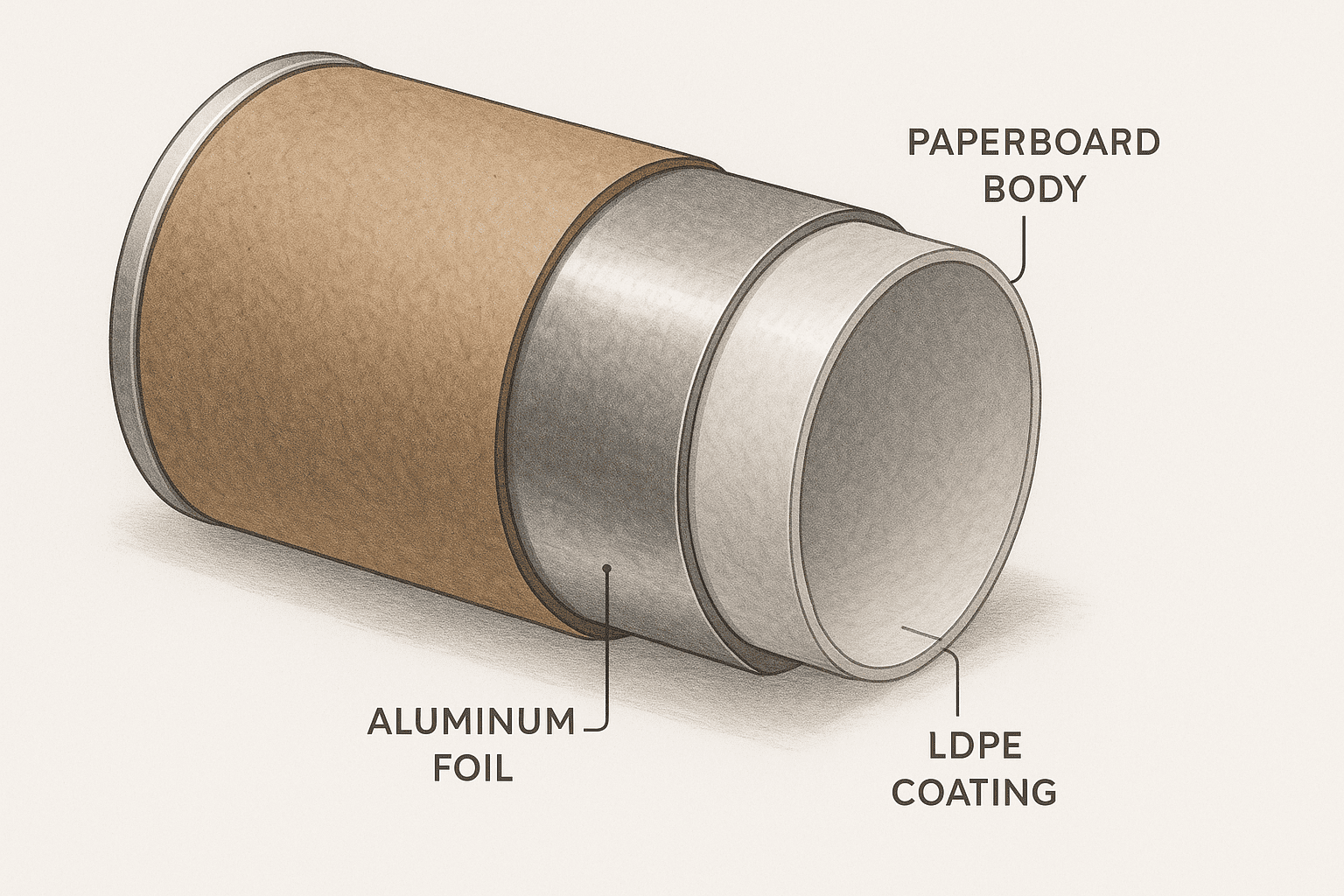

Composite Cans (Limited Use Cases)

You see these for Pringles-style stackable chips. The structure is paperboard body (recycled fiber, 1.5-2mm thick) with an aluminum foil liner (9-12 microns) and LDPE inner coating (30 microns). Metal or plastic ends get crimped on.

Composite cans protect chips from crushing better than any flexible bag. But they cost 3-5x more per unit and create shipping weight issues (a 150g chip bag weighs 5g; a composite can weighs 35g). I only recommend these when the product needs rigid protection or the cylindrical shape is a brand differentiator.

Real-World Failure Modes Nobody Talks About

This section is why I wrote this guide. The academic packaging articles never cover this.

Seasoning Oil Migration Issues

Here’s the failure mode that causes 60% of actual retail complaints: seasoning oil migrates through the inner seal layer over time, weakening the heat seal. No lab test measures this accurately because standard accelerated aging uses dry heat (40°C). Real chips have 3-8% residual oil on the surface.

What happens: the flavoring oils (typically sunflower or palm oil with dissolved spices) slowly penetrate the PE inner layer. After 60-90 days, the seal area becomes plasticized (softened). Then when a pallet shifts during transport, the seals pop open.

I saw this with a barbecue chip line. Their seal strength tested at 2.5 N/15mm at day 0 (good). At day 120, same bags tested at 0.8 N/15mm (fail). The oil had migrated 0.3mm into the seal zone. The solution wasn’t a better barrier—it was switching from LDPE to a medium-density PE (MDPE) inner layer with higher oil resistance. Cost increased $0.002 per bag. Recall costs dropped by $180,000 that year.

Acid Attack on Polyethylene Seal Layers

Citric acid is used in many chip seasonings (salt & vinegar, sour cream, BBQ). Here’s what formulators miss: citric acid in powder form is hygroscopic (absorbs moisture). Inside a sealed chip bag at 25°C, relative humidity rises to 40-60% within 72 hours (from residual potato moisture).

That moisture dissolves trace amounts of citric acid5. The acidic solution then attacks the PE seal layer’s polymer chains. After 90 days, you get micro-cracks in the seal that let oxygen in. The chips start going stale even though the bag still looks sealed.

I consulted for a brand that had perfect shelf life with their original recipe. They reformulated to add "tangy lime" flavor (citric acid + lime oil). Suddenly their 6-month shelf life dropped to 3 months. We solved it by adding a 3-micron SiOx (silicon oxide) coating to the inner layer. That coating is impermeable to both oxygen and acid. Added $0.008 per bag but saved the product line.

Why 60% of Recalls Happen Post-90 Days

Most food brands do 30-day and 60-day shelf life tests. They check microbiology, moisture content, and sensory scores. Everything passes. They launch the product. Then 4 months later, retailers start reporting stale chips.

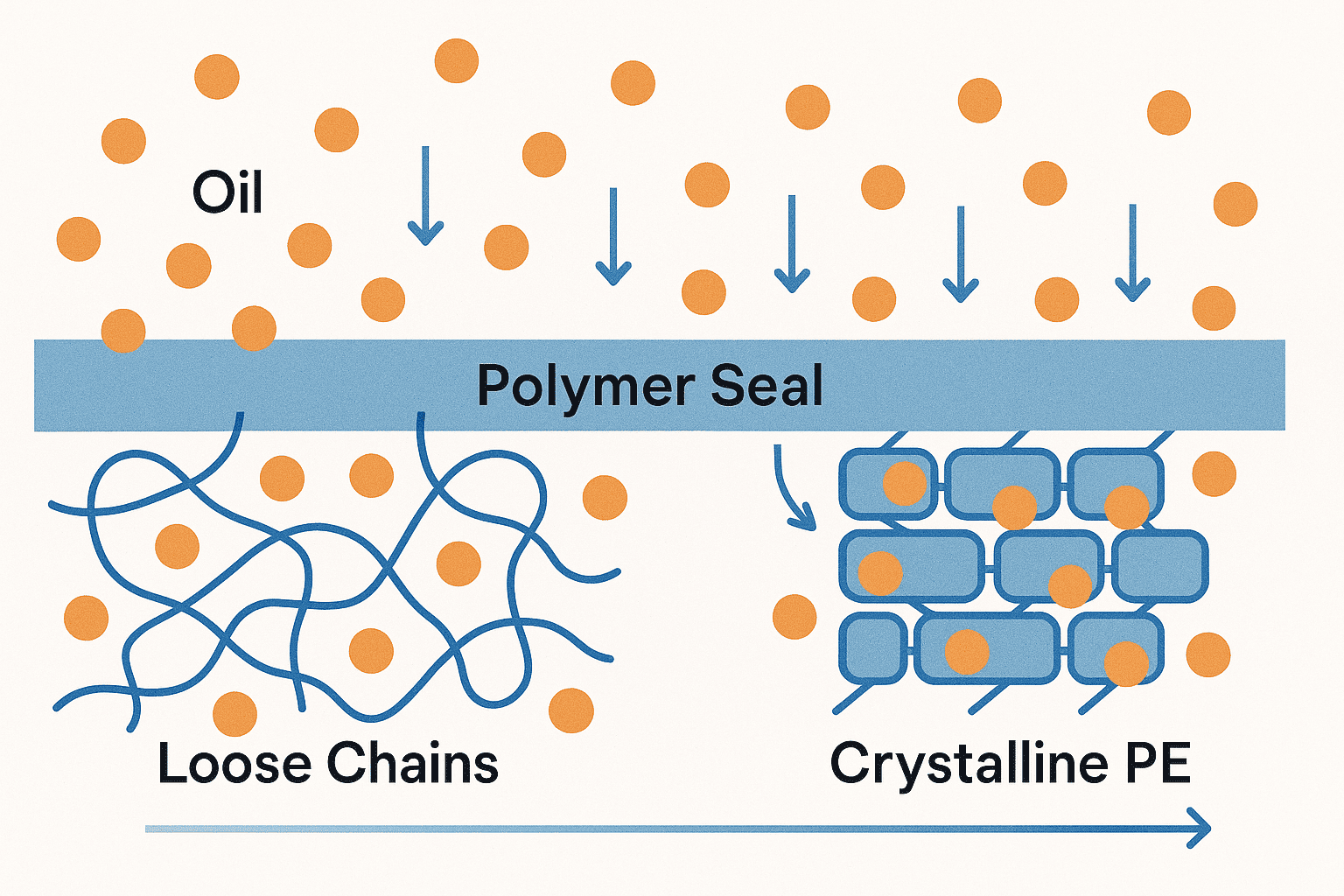

The reason is simple: PE crystallinity increases over time. When PE film is first extruded, it’s about 45-50% crystalline (the polymer chains are partially aligned). Over 3-4 months at room temperature, it slowly crystallizes further to 55-60%. This makes the film stiffer and more brittle.

If your seal strength was borderline acceptable at day 0 (say 1.8 N/15mm when spec calls for 1.5 N/15mm minimum), it might drop to 1.2 N/15mm at day 120 as the PE crystallizes. Now it fails.

The fix is simple but ignored: do seal strength testing6 at 90 and 120 days, not just 0 and 30. If your day-90 seal strength is below 2.0 N/15mm, increase your seal bar dwell time by 10-15 milliseconds or raise temperature by 5°C. Most brands don’t discover this until after a recall.

Printing Technologies for Chips Packaging

I need to address this because printing is where many sustainable packaging projects fail. You can have the perfect material structure, but if the printing doesn’t work, you can’t launch.

Rotogravure Trade-offs

For chip bags, you have two realistic options:

Rotogravure (gravure printing):

- Uses engraved metal cylinders (one per color)

- Cylinder cost: $800-1,500 per color

- Minimum economic run: 500km of film (~50,000-100,000 bags depending on size)

- Print quality: Excellent (comparable to magazine photos)

- Line speed: 150-400 meters/minute

- Best for: High-volume brands with stable designs

Digital Printing for Short Runs

Digital (inkjet or toner-based) is emerging for chip bags, I see digital making sense for:

- Test market launches (500-2,000 bags)

- Personalized or regional SKUs

- Co-packing operations with high SKU variety

For mainstream production, gravure remains more cost-effective above 10,000 bags per run.

Emerging Disruptions in Chips Packaging

This is where the industry is heading, and most Western companies are missing it.

Micro-Perforation Moisture Control

Here’s the innovation: controlled micro-perforations (60-120 microns diameter, 1-3 holes per 100 cm²) that let moisture vapor escape while keeping oxygen below 1 cc/m²/day. This sounds contradictory, but it works because water vapor molecules (2.75 Ångströms) are smaller than oxygen molecules (3.46 Ångströms) at the perforation edges.

Why this matters: traditional chip bags trap moisture from the potato starch. After 60 days, the inside of the bag can hit 70-80% RH even though the chips started at 2% moisture. The chips absorb that humidity and get soft. With micro-perforations, the RH stays below 50% and shelf life extends from 6 months to 9-12 months.

Three suppliers in South Korea and Taiwan perfected this in 2021. I’ve tested their films. Shelf life improvement is real. But they require specialized laser perforation equipment (most Western converters don’t have this) and the perforation pattern needs to be precisely mapped to avoid the seal zones.

Asian Suppliers’ Quiet Innovation

While European and North American film producers chase compostable substrates, Asian manufacturers focused on solving the actual problems: better barriers at lower thickness, better machine compatibility, better oil resistance.

I source films from both Western and Asian suppliers. Here’s what I observe:

| Feature | Western Suppliers | Asian Suppliers |

|———|——————|————-er–|

| Barrier innovation | Focus on bio-based | Focus on thinner metallization |

| Machine compatibility | Test on lab equipment | Test on client’s actual lines |

| Customization MOQ | 10+ tonnes | 3-5 tonnes |

| Lead time (custom) | 10-14 weeks | 6-8 weeks |

| Price | Higher | 15-30% lower |

The gap is closing as Western suppliers improve, but Asian suppliers currently have an edge in practical performance optimization.

Why Compostable Films Still Fail Above 40% Humidity

I want to be honest about this because I sell sustainable packaging: current compostable films (PLA, PBAT, cellulose-based) have a critical weakness in humid environments.

The problem is water vapor transmission rate (WVTR). Traditional metallized BOPP has WVTR of 0.5-2 g/m²/day. Most compostable films are at 8-20 g/m²/day. That’s fine for dry products or short shelf life. For chips that need 6-9 months, it’s problematic.

Above 40% ambient humidity (common in Southeast Asia, coastal regions, summer in most places), compostable films absorb moisture themselves. The film gets 5-8% heavier. This throws off VFFS machine timing (the film density changes) and causes seal inconsistencies.

I tested seven compostable chip bag films in Thailand (85% RH average). All seven had seal failure rates above 12% after 90 days. The same films in Arizona (20% RH) had failure rates under 3%.

The solution isn’t abandoning compostables—it’s developing hybrid structures. For example, a 90% compostable film with a 10% EVOH (ethylene vinyl alcohol) barrier layer that gets separated during industrial composting. Or regional solutions: compostables for dry climates, recyclable metallized for humid climates.

How to Choose the Right Packaging (Buyer’s Checklist)

After all this technical detail, here’s my practical advice for making the decision:

Step 1: Know Your Co-Packer’s Equipment

Call them. Ask specifically: "What VFFS machine brand and model do you run?" Then ask: "What films have you successfully run in the past 6 months?" Don’t design packaging around theoretical capabilities.

Step 2: Match Volume to Printing Method

- Under 20,000 bags/year: Digital or small-run flexo

- 20,000-500,000 bags/year: Flexographic

- Above 500,000 bags/year: Consider rotogravure

Step 3: Test Actual Shelf Life, Not Lab Conditions

Run a 90-day and 120-day test with real chips in real storage conditions. Include one elevated temperature cycle (35°C for 7 days) to simulate summer warehousing.

Step 4: Prioritize Oil Resistance Over Generic "Barrier" Claims

If your chips have over 20% fat content or bold seasonings, specify that you need oil-resistant inner layers (MDPE or treated PE). Ask for test data on oil migration, not just oxygen permeability.

Step 5: Start with Proven Structures, Then Optimize

Don’t start with a revolutionary new material. Start with metallized OPP7/PE laminate (the industry standard). Get your production running smoothly. Then incrementally test one variable at a time: thinner gauge, recycled content, better barrier layer, etc.

For my clients, I recommend starting with a 75-micron PET/metallized BOPP/PE structure from an established Asian supplier. Once production is stable, we introduce 30% PCR (post-consumer recycled) content in the PE layer. Then we test reducing thickness to 68 microns. This stepwise approach reduces risk.

Frequently Asked Questions About Chips Packaging

1. Can I use 100% recyclable materials for chips?

Yes, but with trade-offs. Mono-material PE structures (all-PE, no aluminum, no PET) are recyclable through store drop-off programs. But barrier performance is lower (oxygen transmission 5-10x higher than metallized films). Shelf life drops from 9 months to 4-6 months. This works for high-turnover products or brands that emphasize sustainability over extended shelf life.

2. How much does chips packaging cost per bag?

For a standard 50g chip bag (180mm x 250mm), costs range from $0.03-0.12 per bag depending on structure and volume:

- Basic 3-layer laminate, rotogravure, 500k+ volume: $0.03-0.04

- Premium 5-layer coex, flexo, 50k volume: $0.08-0.12

- Compostable film, digital print, 10k volume: $0.15-0.25

3. What’s the shelf life difference between metallized and non-metallized films?

Metallized films (aluminum layer 6-12 nanometers thick) typically provide 9-12 months shelf life for chips. Non-metallized clear films with SiOx or EVOH barriers provide 4-6 months. The aluminum completely blocks light and reduces oxygen transmission 10-15x compared to transparent barriers.

4. Why do some chip bags have a shiny interior and others don’t?

Shiny interior = reverse-printed metallized film (printing on back of metallized layer). Dull interior = surface-printed with separate aluminum layer or outer metallization. Reverse printing protects ink from abrasion but costs 10-15% more. Most brands use surface printing.

5. Can I get resealable zippers on chip bags?

Yes, but it adds $0.02-0.04 per bag and requires different VFFS equipment (zipper applicator attachment). Resealable bags make sense for larger sizes (200g+) where consumers eat multiple servings. For single-serve (25-50g), the cost isn’t justified.

6. How do I test if a film will work on my co-packer’s machine?

Ask your film supplier for a 50-100 meter sample roll. Send it to the co-packer for a trial run. Pay for 2-4 hours of machine time. Run at full speed and check: jam frequency, seal consistency, bag formation quality, and filling accuracy. This $500-1,000 test prevents a $50,000 mistake.

Conclusion

Chips packaging isn’t about finding the "best" material. It’s about finding the material that works with your specific machinery, product chemistry, and distribution environment. The brands that succeed don’t chase perfect lab specs—they optimize for real-world performance across the entire system. Start with proven structures, test rigorously, and evolve incrementally. That’s how you avoid burning $2 million on films that can’t seal.

-

Find out how multi-layer structures enhance food packaging performance and shelf life. ↩

-

Understand the role of barrier performance in protecting food products from spoilage. ↩

-

Discover the latest innovations in sustainable packaging solutions that can benefit your brand. ↩

-

Understand the differences between coextruded films and laminates in packaging applications. ↩

-

Understand the impact of citric acid on packaging materials and how to prevent seal failures. ↩

-

Learn about the importance of seal strength testing and how it impacts product quality. ↩

-

Explore the advantages of metallized OPP, the industry standard for chip packaging, and its role in maintaining freshness. ↩