Most people think chip packets are made of aluminum foil. They’re wrong. The truth is more interesting—and it matters if you’re buying packaging for your product.

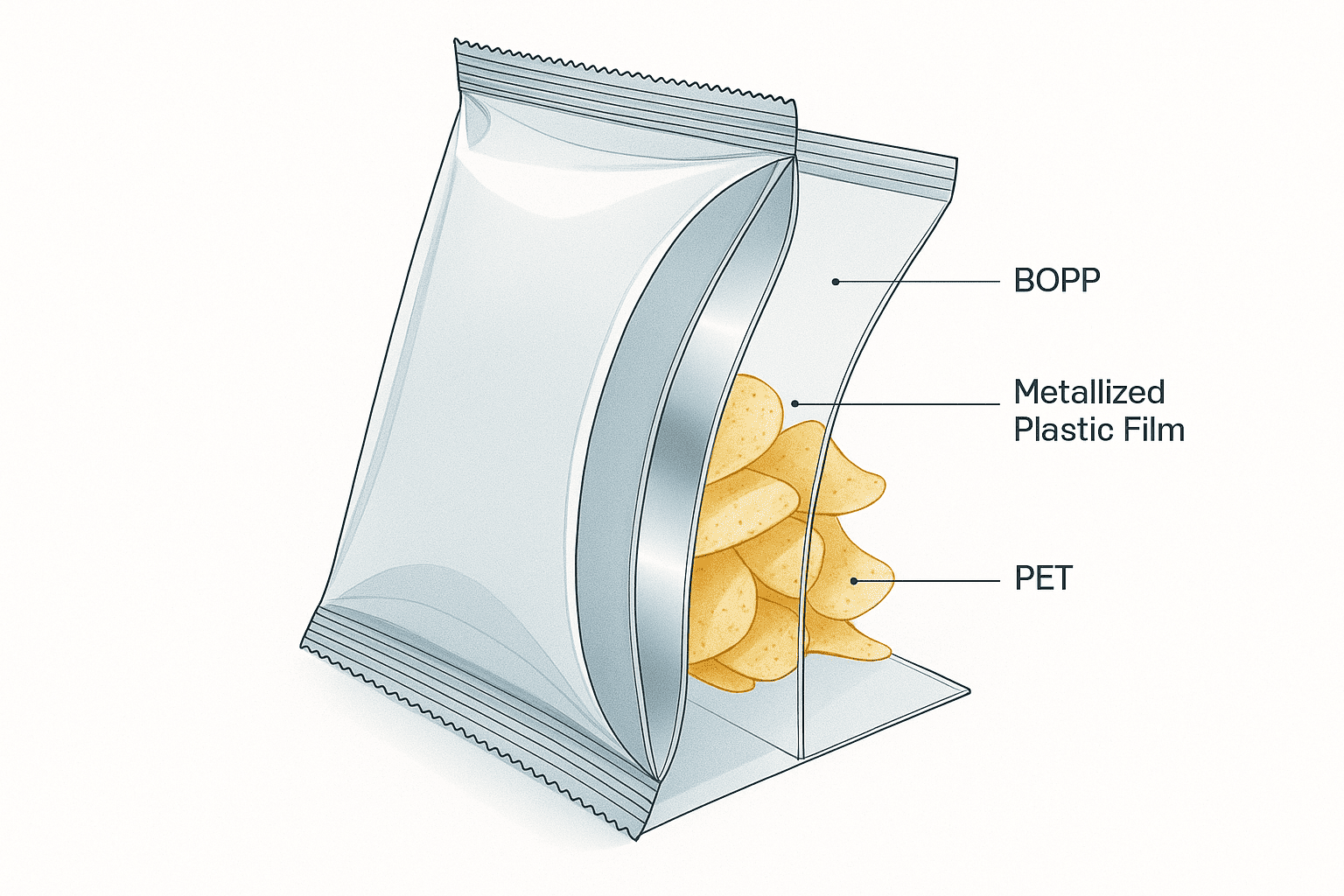

Modern chip packets use metallized plastic film, not aluminum foil. Pure aluminum foil packaging1 for chips commercially died in the 1990s. Today’s bags are multi-layer plastic structures with a thin metal coating that provides better barrier performance2 at lower cost. The "foil" appearance comes from vacuum-deposited aluminum on plastic substrates like BOPP or PET.

This shift wasn’t random. The packaging industry discovered that barrier mathematics—not material thickness—determines shelf life. But many buyers still use outdated specifications from the foil era. That costs brands millions in reformulation and waste.

Why Did Aluminum Foil Disappear From Chip Packaging?

The chip industry loved aluminum foil in the 1970s and 1980s. It blocked oxygen and moisture perfectly. But it had fatal flaws.

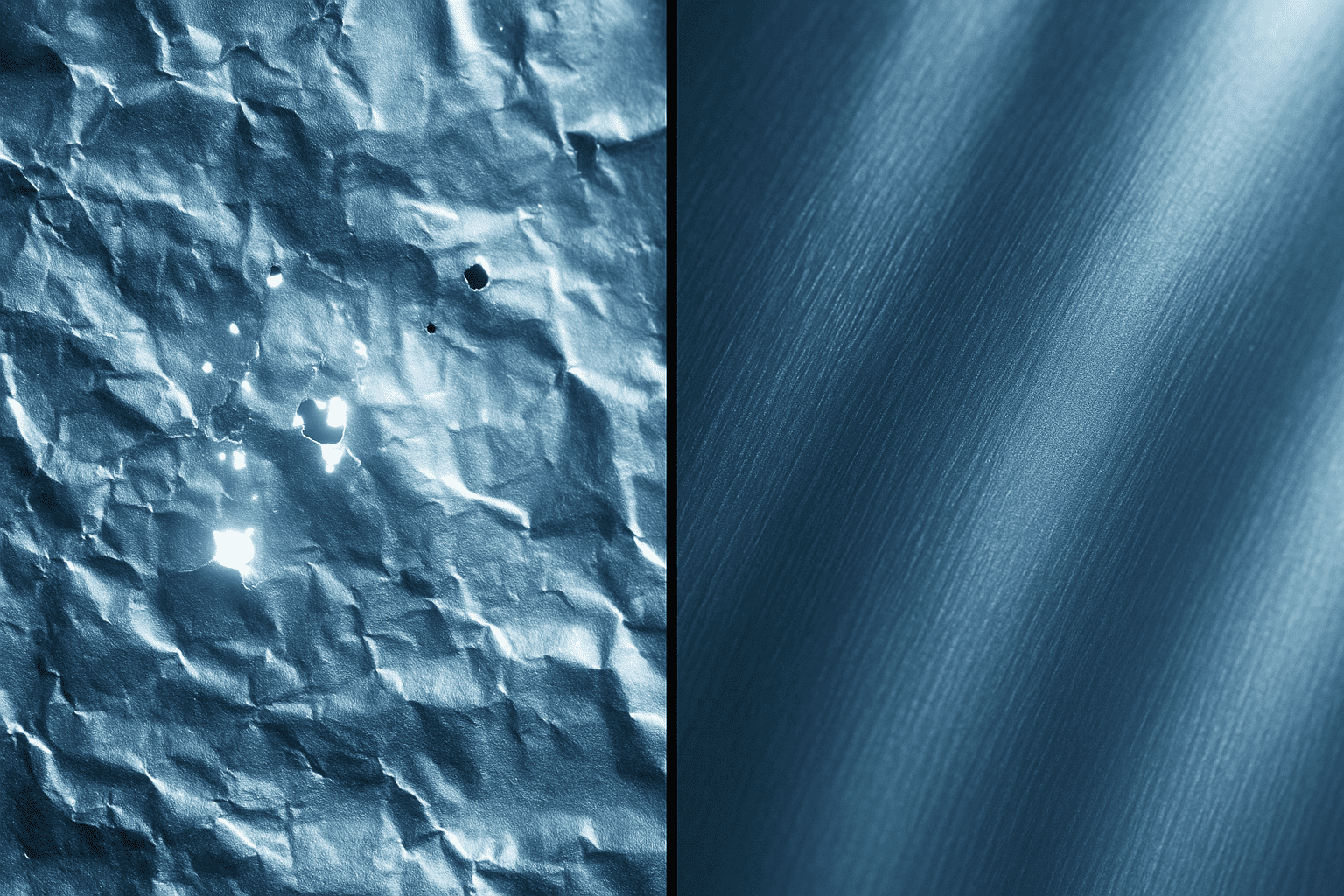

Aluminum foil packaging stopped being economically viable for chips in the early 1990s when manufacturers discovered that 12-micron metallized BOPP (biaxially oriented polypropylene) with proper sealant layers could outperform traditional foil laminates by 40% in cost-efficiency while maintaining equivalent barrier properties. The foil’s brittleness caused pinhole defects during high-speed packaging, leading to unacceptable failure rates.

Real aluminum foil tears easily. When packaging lines run at 120 bags per minute, even microscopic tears become disasters. One pinhole ruins the entire barrier. Oxygen seeps in. Chips go stale.

Metallized films solved the brittleness problem. Manufacturers vacuum-deposit a layer of aluminum atoms onto plastic film. The layer is incredibly thin—about 300-500 angstroms. That’s roughly 0.00003 millimeters. But it’s enough to create an effective barrier.

The plastic carrier film (usually BOPP or PET) provides mechanical strength. The aluminum layer provides the barrier. This combination beats pure foil in almost every metric that matters for production.

The Material Structure That Replaced Foil

Modern chip bags typically use a three-layer structure. The outside layer is often matte BOPP at 18-20 microns thick. This provides printability and structural integrity.

The middle layer is VMPET3 (vacuum metallized polyester) at 12 microns. VMPET is where the barrier magic happens. That thin aluminum coating blocks oxygen and moisture vapor transmission.

The inner layer is LDPE4 (low-density polyethylene) at 40-60 microns. This creates the heat seal and provides a food-safe contact surface.

Here’s the critical data that procurement teams often miss:

| Material Structure | Total Thickness | OTR (cc/m²/24hr) | WVTR (g/m²/24hr) | Cost Index |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Al Foil Laminate | 90-100 microns | <0.5 | <0.5 | 100 |

| Matte BOPP/VMPET/LDPE | 70-80 microns | 1-3 | 1-2 | 60 |

| Premium BOPP/AlOx/LDPE | 75-85 microns | 0.8-2 | 0.8-1.5 | 75 |

The OTR (oxygen transmission rate5) and WVTR (water vapor transmission rate6) numbers tell the real story. Metallized films come close enough to foil’s barrier performance for most applications. And they cost 25-40% less.

What Most Buyers Get Wrong About Chip Bag Specifications

I’ve watched three major snack brands reformulate products because their packaging buyers confused fundamental barrier concepts. Nobody admits this publicly. But it happens constantly.

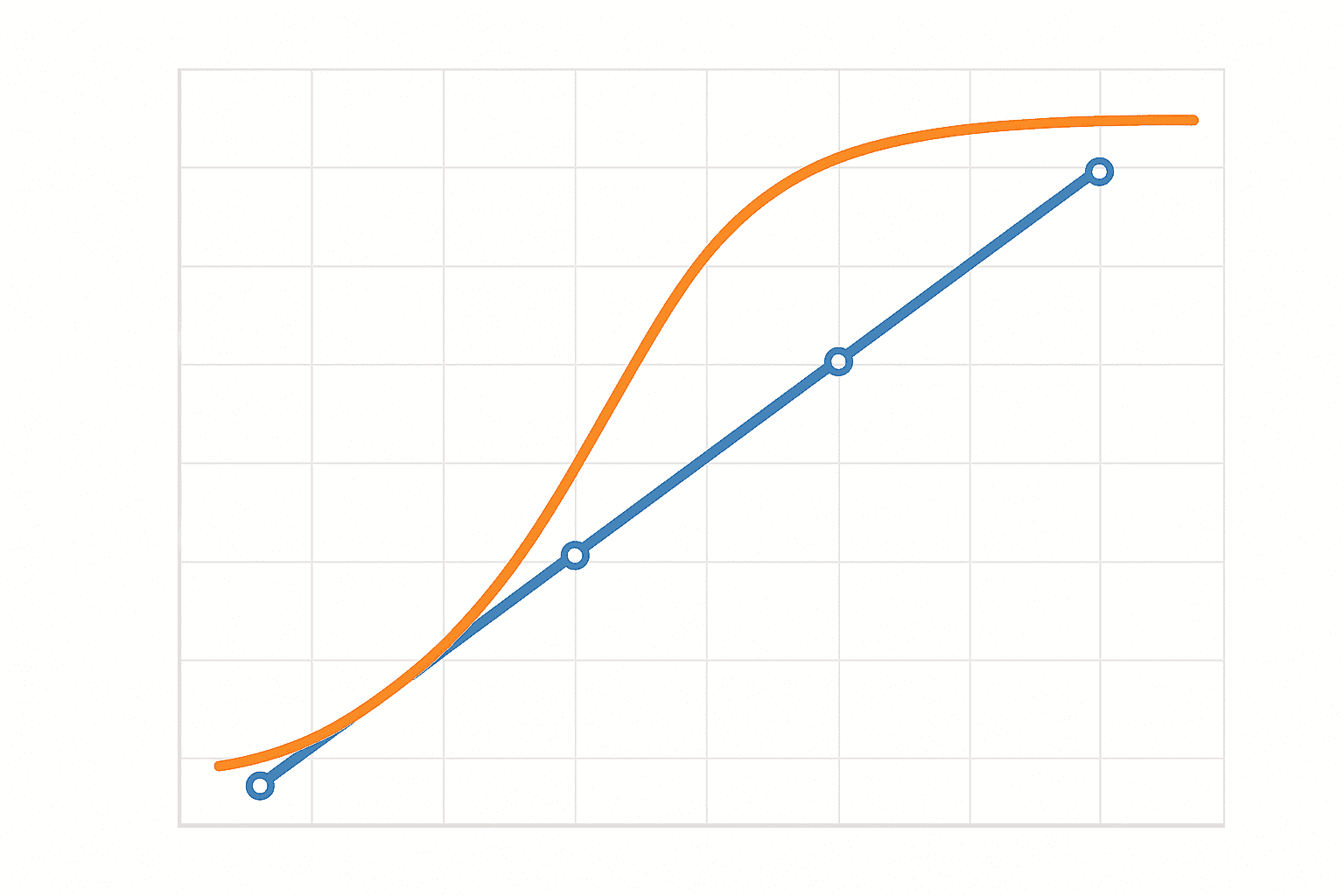

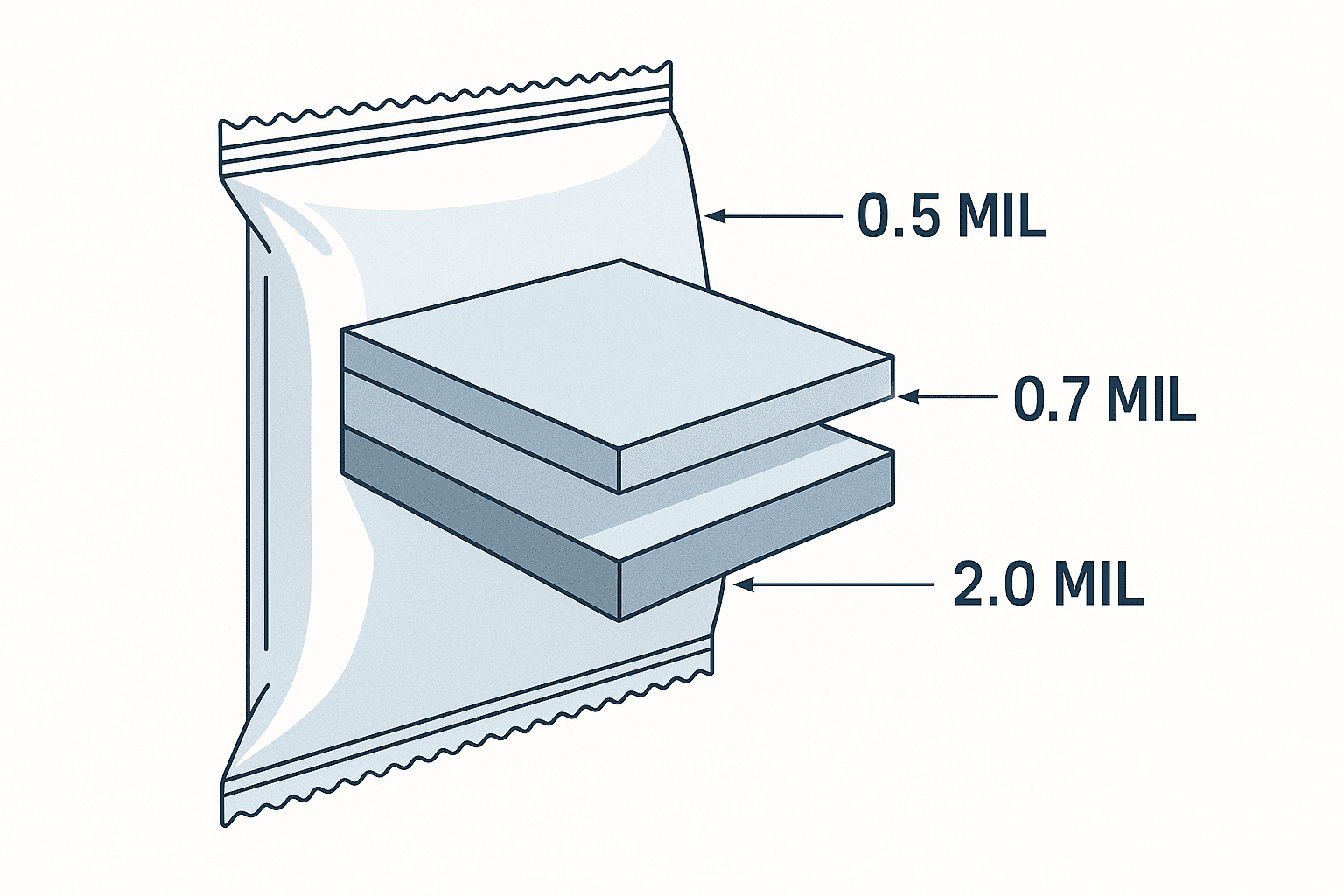

The most common specification error is using mil thickness as a proxy for barrier performance. This metric originated in the aluminum foil era when thickness directly correlated with barrier properties. With metallized films, a 12-micron VMPET structure can outperform a 25-micron non-metallized film by 500% in oxygen barrier, yet buyers reject the better option because it "feels thinner" and doesn’t meet their outdated thickness minimums.

The physics is straightforward. Barrier performance depends on material density and molecular structure, not just thickness. A thin layer of aluminum atoms creates tortuosity—oxygen molecules have to take a longer, more complex path through the material. This dramatically improves barrier efficiency7.

Here’s what actually matters for chip packaging barrier performance:

Oxygen Transmission Rate (OTR): This measures how much oxygen passes through the material. For potato chips, you want OTR below 5 cc/m²/24hr. Premium structures achieve 1-2 cc/m²/24hr.

Water Vapor Transmission Rate (WVTR): This measures moisture permeability. Chips go soggy above 3 g/m²/24hr. Good metallized films achieve 1-2 g/m²/24hr.

Seal Integrity: This is where production reality hits. You can have perfect barrier film, but if your seals fail, everything fails. LDPE sealant layers need proper corona treatment8. The surface energy must hit 38-42 dynes/cm for reliable seals.

The Corona Treatment Problem Nobody Talks About

Corona treatment oxidizes the film surface to improve adhesion. But it degrades over time. I’ve seen it drop from 40 dynes/cm to 32 dynes/cm in 48 hours under humid conditions.

That’s why I walk production floors at 2 AM. You catch these issues before they ruin a month’s inventory. The packaging buyer sitting in an office 500 miles away never sees this. Their plant manager does—and appreciates when suppliers explain it in terms that make them look competent to their VP.

The corona treatment drop causes delamination. The metallized layer separates from the sealant layer. Moisture migrates through the gap. Your barrier performance collapses.

Testing protocol matters enormously. You need to measure surface energy at the production line, not just in the lab. You need to verify seal strength under accelerated aging conditions. And you need to communicate these results to decision-makers who understand why they matter.

Are Chip Packets Actually Recyclable?

This is where things get uncomfortable. The honest answer is no—not in most municipal recycling systems.

Traditional chip packets combining metallized plastic layers cannot be mechanically recycled because the aluminum coating contaminates plastic recycling streams and the multi-layer structure cannot be economically separated. The "crinkle test" (crush the material—if it bounces back, it’s not recyclable) accurately identifies these non-recyclable metallized films. Currently, less than 5% of chip packaging enters specialized recycling programs9 that can handle metallized structures.

The metallized layer creates the problem. Recycling facilities sort plastics by resin type. But metallized film is neither pure plastic nor pure metal. The aluminum content is too low to recover economically. The plastic is contaminated with metal.

Some municipalities accept metallized packaging in specialized streams. But these programs are rare. Most chip bags end up in landfills or incinerators.

The Compostable Film Hype vs Reality

Every sustainability conference features someone pitching compostable chip packaging10. The materials exist. They work in labs. They fail in real markets.

I’ve tested compostable structures extensively. Here’s what the marketing materials don’t tell you:

Barrier performance collapse in humidity: Compostable films based on PLA or cellulose lose 60-80% of their barrier properties above 70% relative humidity. That makes them useless for distribution in tropical or coastal climates.

Equipment compatibility disasters: Compostable films typically require 15-20% slower line speeds and different seal parameters. Converting existing packaging lines costs $200,000-500,000 per line. Most brands can’t justify that investment.

Home composting failures: Materials certified for "industrial composting" need 140°F temperatures and controlled moisture. Home compost piles rarely achieve this. The bags persist for years, frustrating consumers.

The companies quietly testing hybrid structures that actually work on existing equipment—those are the ones who’ll survive the next decade. Not the ones chasing compostable film theater.

What Should You Specify for Chip Packaging Today?

If you’re buying packaging for potato chips or similar snack products, here’s my practical recommendation framework.

For standard distribution (12-month shelf life target): Specify matte BOPP 18-20 microns / VMPET 12 microns / LDPE 50-60 microns. Require OTR <3 cc/m²/24hr and WVTR <2 g/m²/24hr. Insist on seal strength testing at 72 hours post-production (not immediately after sealing).

For my clients in the premium snack category, I recommend structures using AlOx (aluminum oxide) coating instead of VMPET. AlOx provides slightly better barrier performance and improved transparency. This matters for products where package appearance drives purchase decisions.

The critical specifications that procurement teams often omit:

Corona treatment requirements: Specify minimum 38 dynes/cm surface energy at time of lamination, verified by dyne pens or contact angle measurement.

Nitrogen flush parameters: Residual oxygen should be <2% post-filling. Many contracts don’t specify this, leading to oxidation failures blamed on packaging when filling is the culprit.

Seal width and temperature: Minimum 8mm seal width, seal temperature 140-160°C for LDPE sealants. Verify seal integrity11 with burst testing, not just visual inspection.

When Sustainability Actually Matters to Your Bottom Line

I tell clients to ignore sustainability theater. Focus on sustainability math that improves economics.

Mono-material recyclable structures exist. They use specialized polyethylene formulations with barrier additives. The barrier performance doesn’t match metallized films—typically 5-10x worse. But for products with 3-6 month shelf life requirements, they work.

The business case: Mono-PE structures qualify for certain recyclability labels. In markets like Germany or California, this can justify 5-10% price premiums. The material costs 15-20% more than metallized film, but the retail price premium covers this easily.

I’ve helped three brands transition to mono-PE structures for regional product lines. The key is honest assessment of shelf life requirements. Most chips don’t actually need 18-month shelf life. They turn over in 45-60 days. You’re over-engineering the barrier.

Common Questions About Chip Packet Materials

1. Can I tell if a chip bag is foil or metallized plastic by looking at it?

No. Visually they’re nearly identical. The only reliable way is to attempt tearing it. Pure aluminum foil tears in a straight line and doesn’t stretch. Metallized plastic stretches before tearing and shows a plastic film underneath the metallic layer. Most modern bags are metallized plastic.

2. Why do some chip bags feel thicker than others?

Thickness variation comes from the LDPE sealant layer, not the barrier layer. Manufacturers adjust sealant thickness based on filling equipment, product shape, and distribution requirements. Thicker doesn’t necessarily mean better protection—barrier performance depends on the metallized layer quality.

3. Is the metallic layer in chip bags safe for food contact?

Yes. The metallized layer never touches food directly. The LDPE inner layer provides the food contact surface. Both VMPET and LDPE are approved food-contact materials under FDA and EU regulations. The aluminum coating is food-grade and applied under controlled conditions.

4. Can chip bags be recycled if I remove the metallized layer?

No. The layers are laminated together with adhesive. Separation is impossible without specialized industrial equipment. Even if you could separate them, the residual adhesive would contaminate both streams. Put used chip bags in regular trash unless your municipality has specific metallized film recycling programs.

5. Why don’t manufacturers just use thicker plastic instead of metallization?

Barrier performance doesn’t scale linearly with thickness. A 100-micron non-metallized plastic film12 has worse oxygen barrier than a 12-micron metallized film. You’d need 500+ micron thickness to match metallized performance—making bags too stiff and expensive to be practical.

Conclusion

Chip packets aren’t foil—they’re metallized plastic films optimized for barrier performance and production efficiency. The buyers who understand barrier mathematics instead of relying on outdated thickness metrics make better decisions. Focus on OTR/WVTR data, equipment compatibility, and honest sustainability assessments. That’s how you avoid the costly mistakes I see brands make every year.

-

Learn about the historical shift from aluminum foil to modern packaging solutions. ↩

-

Understand the key elements that determine packaging effectiveness and shelf life. ↩

-

Learn about the benefits of VMPET in creating effective barrier films. ↩

-

Explore the properties of LDPE and its importance in food safety. ↩

-

Discover how OTR impacts the freshness of packaged foods and its measurement. ↩

-

Find out why WVTR is crucial for maintaining product quality in snacks. ↩

-

Understand the metrics that define barrier efficiency and their implications. ↩

-

Understand how corona treatment enhances adhesion in packaging materials. ↩

-

Find out how specialized programs can improve recycling rates for complex materials. ↩

-

Learn about the limitations of compostable materials in real-world applications. ↩

-

Discover how seal integrity affects product freshness and shelf life. ↩

-

Explore how metallized plastic film enhances packaging efficiency and barrier performance. ↩